eDNA of Sheriff’s Pond

By Jesse Ausubel

Environmental DNA (eDNA) is DNA shed by animals into the environment. Sources include cells sloughed from body surfaces, body wastes, and tissue remnants following predation, death, or injury. eDNA is a bit like dandruff. DNA consists of long strands of four chemical compounds: cytosine (C), adenine (A), guanine (G), and thymine (T). Researchers can use strands of about 100 “letters” from variable parts of the genome, like a long telephone number, to identify the species of animal from which the DNA comes. In aquatic environments very long and thus heavy pieces of eDNA sink from the water column into the mud, and other lengthy strands of DNA are degraded into pieces too short for making a reliable identification. Acidity, heat, and light can speed eDNA degradation, and bacteria eat eDNA. A rule of thumb is that eDNA sufficient for reliable identification lasts about 24 hours.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) is DNA shed by animals into the environment. Sources include cells sloughed from body surfaces, body wastes, and tissue remnants following predation, death, or injury. eDNA is a bit like dandruff. DNA consists of long strands of four chemical compounds: cytosine (C), adenine (A), guanine (G), and thymine (T). Researchers can use strands of about 100 “letters” from variable parts of the genome, like a long telephone number, to identify the species of animal from which the DNA comes. In aquatic environments very long and thus heavy pieces of eDNA sink from the water column into the mud, and other lengthy strands of DNA are degraded into pieces too short for making a reliable identification. Acidity, heat, and light can speed eDNA degradation, and bacteria eat eDNA. A rule of thumb is that eDNA sufficient for reliable identification lasts about 24 hours.

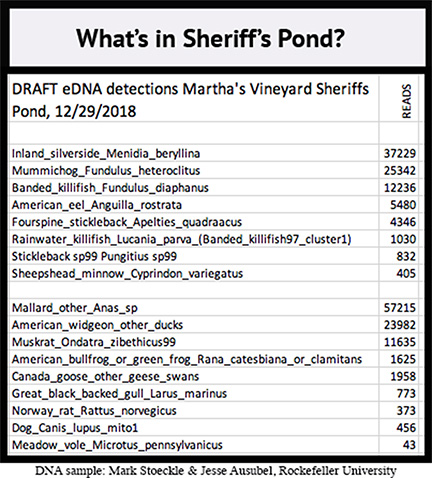

During the frigid afternoon of 29 December 2018, I collected a liter of water from the small bridge at the northern end of Sheriff’s Pond, where it drains to the salt marsh and the sea. At my home in Oak Bluffs, I pumped the water through something like a coffee filter and kept the filter cool in a clean jar. With my colleague Mark Stoeckle at The Rockefeller University in New York City, I later extracted the DNA from the sediment on the filter, used special chemicals called primers to grab only the DNA that came from vertebrates, sequenced all these pieces or “reads” of eDNA, and matched the reads against genetic libraries. The number of reads corresponds to the recent abundance of the animal in Sheriff’s Pond. Not including salaries, the total direct cost of the work for chemicals and other materials was about $50.

What did we learn for $50? We found DNA from eight species of fish and nine other vertebrates. Most of the fish DNA came from small minnow-like animals that like brackish water: silverside, mummichog, and its cousin the banded killifish. DNA of American eel was also quite abundant. DNA also came from four birds—mallard, widgeon, goose, and black-backed gull, with mallard and widgeon abounding. Also plentiful was muskrat DNA. Scant DNA of frog, brown (Norway) rat, dog, and vole completed the roster. Of the 17 species, only the four bird species were visible, although a dog would have been easy to sight. In summer, we would expect to find DNA of more aquatic species—humans are not the only seasonal animals. And a lot more dog DNA.

eDNA revolutionizes the ability for people to know, affordably, what animals live in or use the waters near them. eDNA will be a routine component of fish stock assessment, detection of invasive species, and monitoring effects of coastal storms and climate change. Collecting eDNA, say, once each month would create a true natural history of Sheriff’s Pond and other fresh and salt water bodies of Martha’s Vineyard.

Jesse Ausubel is an environmental scientist working at The Rockefeller University and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and is best known for having founded and led the worldwide Census of Marine Life (2000-2010).

DNA sample: Mark Stoeckle & Jesse Ausebel, Rockefeller University