By Adam R. Moore

“This is going to be your desk!” said Joe Rogers, as he gestured to a plank of pitch pine, fresh off the sawmill.

I smiled, and took a closer look at the plank and at the stack of lumber. Some of the boards were mainly heartwood, the somewhat rot-resistant, aromatic wood at the core of each mature pitch pine. Red in color, the heartwood boards are generally clear of knots, and the most durable wood that the pitch pine offers. Other boards contained more sapwood, which is more of a cream color, and lacking in the chemicals that confer the natural rot-resistance to the heartwood. Perhaps the most striking wood, though, is the sapwood containing the blue-stain fungus. Many of the logs, and many of the sapwood boards, contain this naturally-occurring, harmless fungus. Although it has no impact on the strength of lumber, the blue stain does impact the appearance. It confers a striking, zebra-striped pattern upon the stained board. Some discerning buyers of wood find this characteristic distinctive, and pay more for the blue-stained lumber.

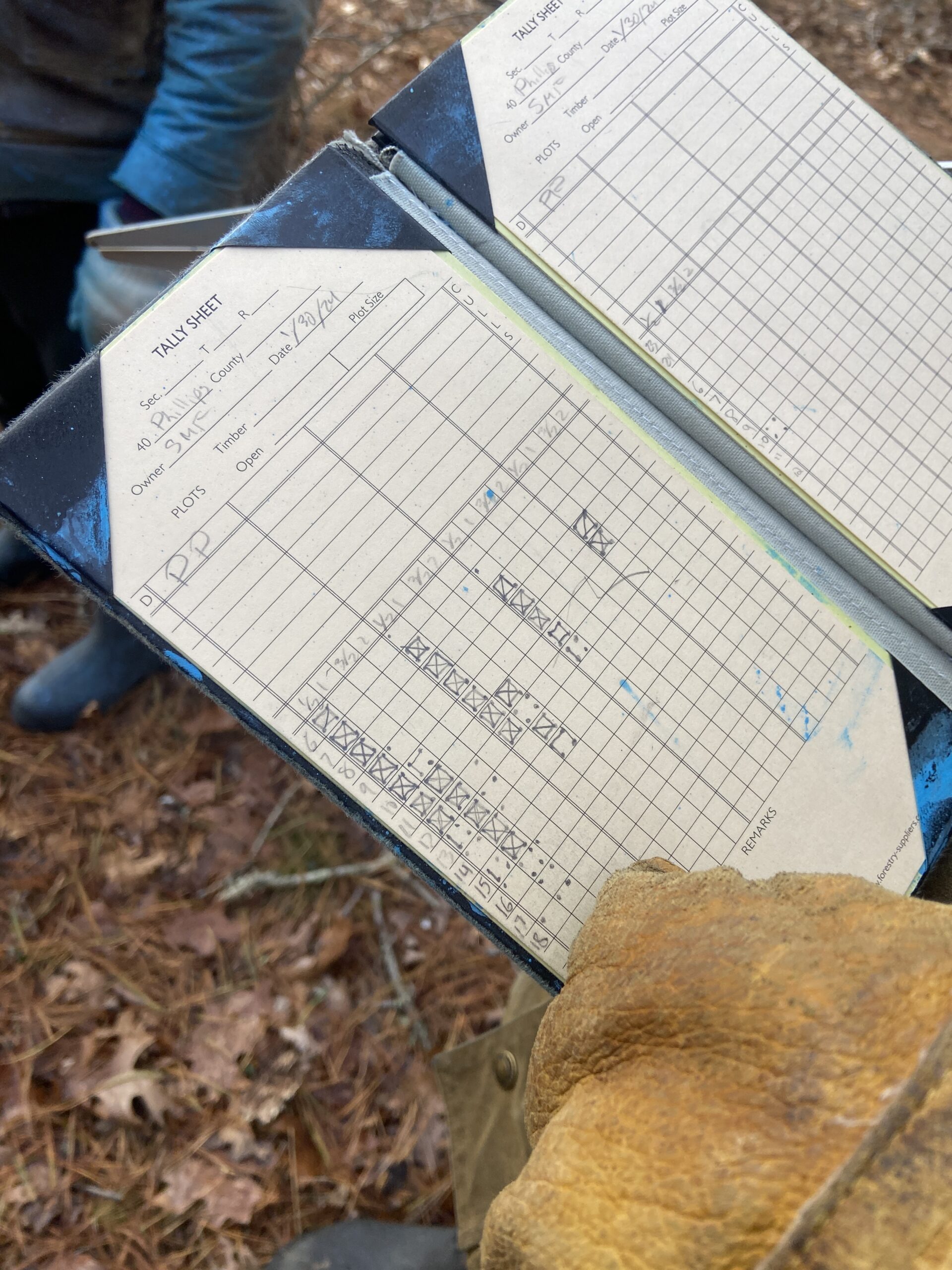

Having tarried enough beside the stack of lumber, I bundled up, and set out into the woods of the Phillips Preserve to mark pitch pines for additional suppression cutting and thinning. I marked, while Noah Froh tallied, and intern Jack Carbon measured the diameter of each marked tree with a pair of giant calipers. I wore old, outdoor clothing that I have sacrificed to the task of marking timber. When marking timber, one uses a one-quart paint can that is outfitted with a spring-loaded, special nozzle, and the whole contraption is referred to as a paint gun. Squeeze the trigger, and the gun sprays blue paint onto the tree to be cut, but also sprays a fine, blue mist onto the hat, face, gloves, clothing, and boots of the person pulling the trigger. Marking timber gives one the opportunity to inspect each tree in the forest. The job is a patient one of pacing through the woods, stopping beside a group of trees, and quietly judging which trees ought to remain and which ought to be cut.

We have been approved for two streams of funding related to forest management. First, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation issued approval for funding of forest stewardship plans for the Phillips Preserve, Caroline Tuthill Preserve, West Chop Woods, and the Reynolds property. This funding will cover staff time devoted to the forest inventory and writing the plan, and totals $19,840. Second, MassWildlife has approved a grant of $75,000 for the logging needed at the Phillips Preserve associated with the southern pine beetle. Here, we will use the funds to hire Cape Cod Firewood to safely and quickly fell and skid the pitch pines that I have marked.

And I have marked a lot of pitch pines. As of press time, I had marked 1,899 pitch pines totaling about 93,485 board feet of sawtimber. These are trees that ought to be removed because they are full of beetle larvae that are ready to emerge as adults when the weather warms up, and trees that ought to be removed because this pine forest is too dense, and thereby very susceptible to infestation. Essentially, each pine tree needs to have the wind blowing around it. This disrupts the chemical communication of the beetles, and may spare some of our mature pitch pines.

I recommend a similar thinning at West Chop Woods. At West Chop Woods, I will be leading a guided public walk on Saturday March 16. At West Chop Woods, the power line right of way offers an excellent place to stack up the logs and deal with the tops of the felled trees (known as “slash”). With respect to this slash, we are seeking a temporary authorization from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection for the use of an air curtain burner. This would enable us to safely and economically dispose of all the treetops, bark, and slabs, and leave behind an attractive site and a forest that has a reduced wildfire risk and is better than we found it.