Sometimes we know when a day of parting shall come. Until that time, each phase of the moon, each setting of the sun, and each toll of the bell bring the inevitable day to the door. All partings, even the bright ones, are touched by a bit of sorrow. At such times, I find myself seeking a means not only to comfort the sorrow, but also to mark the significance. At the latest parting in my life, I found that means in Island history.

My latest partings have been the departures of our two oldest children to college. These are happy occasions, certainly, yet they are also bittersweet. For our second-oldest daughter, Isabel, her parting drew nigh each passing day of the last summer.

We live at Quansoo, on the land of Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation, next door to the antique Hancock-Mitchell House. The final night at home was a lovely September evening, when blue claw crabs paddle in the dark waters of Crab Creek, and fishermen cross the dunes to spend the night angling for striped bass.

The next day, Isabel was to head to college—or rather, Uni, as they say in the United Kingdom. She was bound for Falmouth University, in Falmouth, England. Falmouth is a harbor town in Cornwall, found along the deepwater port of the River Fal, far out on this southwestern peninsula of the island of Great Britain. Falmouth University is a university of the creative arts, with two campuses.

One university campus is in Falmouth, the old campus of the Falmouth Art School, with lovely Georgian buildings, palm trees, and lush gardens of subtropical plants. The other university campus is high atop a hill in the neighboring town of Penryn. Though the Penryn campus is new, Penryn once hosted Glasney College, an ancient, Cornish college that was destroyed by King Henry VIII. Henry used the stones from the college to build Pendennis Castle, which still guards the entrance to Falmouth Harbor. The buildings at the Penryn campus bear the Glasney name in homage to the Cornish school of old. Of the journey Isabel was to make, we all shared a sense of excitement, and also trepidation.

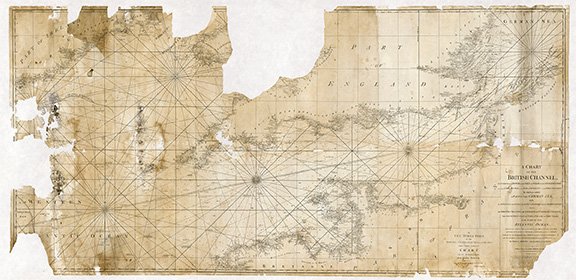

After dinner, I asked everyone to remain seated for a moment. I stepped outside to fetch something from the car. I returned with a nautical chart. Eight feet long, this chart is a facsimile of a 1794 chart of the English Channel. The original belonged to Captain Samuel Hancock, who once lived right next door to us in the Hancock-Mitchell House. In 2011, Laurie Miller found the map while working in the house, stowed above an attic room, covered with centuries of dust and raccoon dung. Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation restored the maps, and gave the restored originals to the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

We set the chart beside the table and inspected it. The chart is finely detailed, with an exquisite rendering of the entire Channel coastlines of both England and France. We looked closely, and I pointed out Penryn—labeled prominently on the map—the very place Isabel would sleep the next night. We marveled that we found her destination quite easily using a map that our neighbor had used, more than two centuries before.

Then I said to Isabel, and to myself, that she was about to become part of a great tradition, a great Quansoo tradition, a great Island tradition. She was about to embark on a trans-Atlantic journey, and thus share in the bonds of so many Islanders before her. She would soon share a common thread that would bond her to those who lived centuries ago, even right next door at Quansoo.

Those who hail from or come to the Island all share the common bond of travel upon or over the seas. For some, sea travel is a regular feature of life—for mariners like Captain Hancock—or for those who commute to the Island daily, lunchbox in one hand and toolbox in the other. Some are intrepid, and set out to seek adventure, or discovery, or fortune. Others travel upon the seas but don’t think much of it; that’s just what is done, and a natural course for anyone who grows up on an Atlantic island.

Captain Hancock’s travels carried him to the salt mines of Cadiz, the courts of St. Petersburg, the markets of Rotterdam, the docks of Liverpool, the streets of London, the dungeon of L’Orient, and the brig of a British prison-ship. And ultimately, his square-rigged vessel carried him back to Martha’s Vineyard.

For her part, Isabel comes back to Martha’s Vineyard in June, and will sail off again at the end of the summer. Of her journey, I am not quite sure what Isabel thought of it all. It may not be clear to her for many years. Yet for me, upon her impending parting, I felt comforted by, and a bit overcome by, a sudden, strong sense of connection to the Quansoo of old.