By Kate Feiffer

As an octogenarian struggling with osteoporosis Elinor Moore Irvin still enjoyed walking the quarter mile from her cabin to get water from the well. “She definitely had a strong personality,” explained her grandnephew Perry Vayo. Vayo, along with his sister, Marie Vayo Greenbaum, worked closely with Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation for over a decade to figure out how best to create a public trail through the 110 acres of land on the north side of Indian Hill Road that would allow for public access without excessively disturbing the natural landscape.

Elinor Moore Irvin’s family purchased the land around the turn of the 20th century and Elinor was born on the Vineyard in 1924. She and her husband, J. Logan Irvin, were both scientists and committed land conservationists who worked primarily in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and spent as much time as they could in their modest one-room cabin on the Vineyard, which had neither running water nor electricity. The couple didn’t have any children and Elinor, who was predeceased by her husband, gave 110 acres of her family’s land to Sheriff’s Meadow in three separate parcels in 1986, 1989, and 2001.

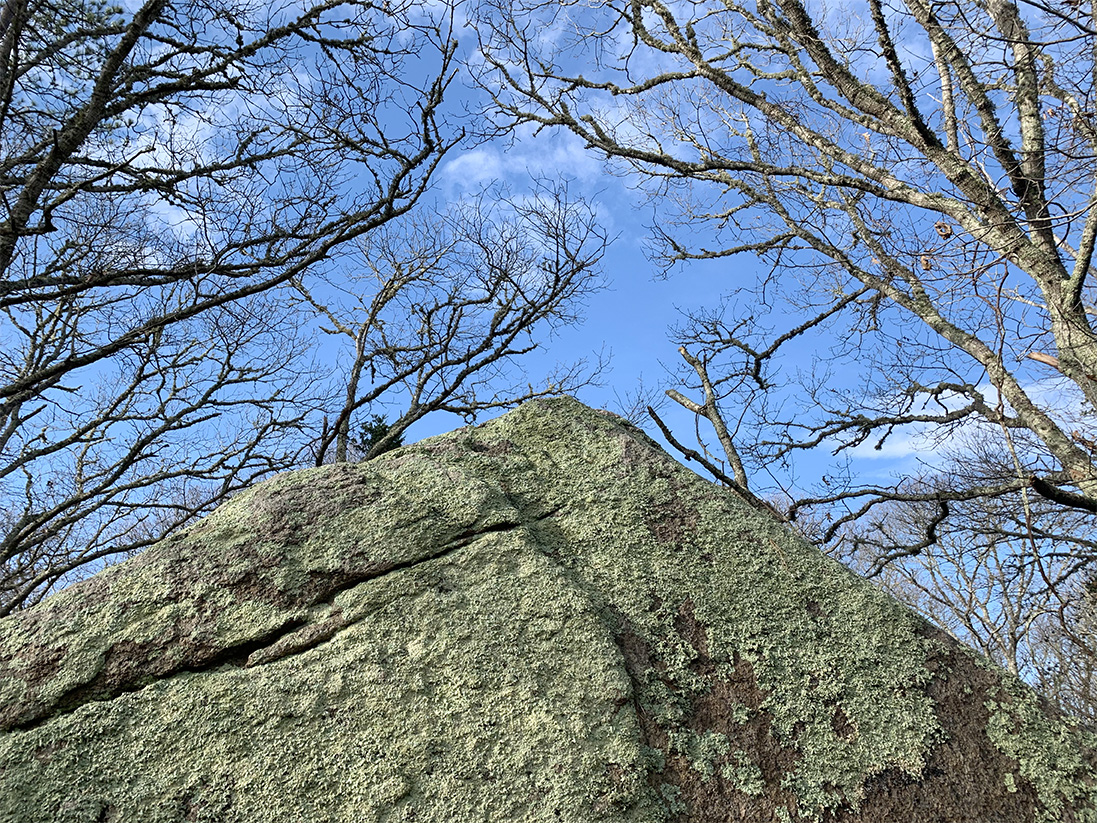

The lengthy process of siting and preparing the 1.5-mile long trail included figuring out which features, like glacial erratic and stonewalls, would be of particular interest to people. “We wanted to ensure that sensitive areas were kept pristine,” said Kristen Geagan, SMF Director of Stewardship.

Joe Rogers building a foot bridge

It was a complicated process that included negotiations with the property’s abutters and permitting from the West Tisbury Conservation Commission. SMF Executive Director Adam Moore expressed his appreciation, “We are grateful to each of our neighbors along this trail, all of whom helped us in making this beautiful trail possible.” The trail, which opened to the public in the fall, is named in honor of Elinor Moore Irvin. It dips and climbs through the woods and walkers pass by several stunning erratics, one with a lone tree growing out of a crevice in the stone. Nearby, there’s a scenic overlook with views across the Vineyard Sound and Buzzards Bay. It is a rigorous walk if you do the entire trail. About a mile and a half in, the trail crosses Obed Daggett Road, over a foot bridge, and passes through a copse of beech trees.

“I think the most splendid area is the beech grove that the trail crosses,” says Adam Moore. “This shady grove invites you to linger a bit.” It’s a bit startling to walk on and emerge out from under a canopy of oaks and beeches into a field of dead and dying red pines. (A sign explains that the trees were a non-native species that were planted by John Daggett and unable to acclimate to the Vineyard’s environment.) The trail, which is not a loop trail, then connects to the network of well-trod Cedar Tree Neck Sanctuary trails.

Of additional interest, Moore points out the abundance of American hollies within the property. “All of which are fairly small and young,” he explains. “These are trees of the future because they are growing in the understory, and are able to become established in the shade of the oaks. When the oaks die, as many have due to moth infestations, the hollies are given a chance to grow and take over. The future of this forest—absent a forest fire—is holly and beech.”

Notable vegetation that can be found on and off the trail includes Indian Cucumber Root, Medeola virginiana, which is an edible root, and Downy Rattlesnake-plantain, Goodyera pubescens, an evergreen herbaceous orchid. “Both the Indian cucumber and Downy Rattlesnake-plantain are the biggest populations I’ve seen anywhere on the Vineyard,” says Kristen Geagan. She adds that there are a lot of common species to be found, such as: huckleberry, greenbrier, high- bush blueberry, white oak, black oak, sassafras, beech, and sweet pepperbush.

The endangered cranefly orchid, Tipularia discolor, can also be found growing along the trail. “The cranefly orchid is a mysterious species of orchid that is easiest to find in the winter. Unlike many other species, the leaves photosynthesize in the winter and fall off in the spring. They have purple pimples on them which make them easy to spot. The flowers are brown and blend into the surroundings so are very hard to see when they bloom in the summer. Not all the leaves produce a flower and some years you won’t see any leaves at all,” explained Geagan, who added, “There’s an older paper that theorized that all MV populations are genetically the same.”

Geagan reminds walkers, “Please never pick or collect flowers that you see growing in the wild!”

Parking is limited by design, as the trail is meant to be used primarily by hikers interested in the geology and ecology of the land.

For family outings, we recommend heading down Obed Daggett Road to the main Daggett Trailhead or up to the end of Indian Hill Road to the Taylor Gate Trailhead.